Global Reporting Initiative: What It Is and How to Do It

GRI stands for Global Reporting Initiative, and is an international independent standards organization that promotes sustainability reporting through the development of global standards for corporate responsibility, including environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting.

GRI Standards are designed to be accessible to any organization, regardless of size or sector. They can be used as part of a company’s annual reporting process, or they can be implemented as part of an organization’s continuous improvement program.

How do the GRI Standards work?

Methodology

The GRI Standards are a modular system comprised of three interconnected series of standards:

- The GRI Universal Standards, which are applicable to all organizations on a broad level;

- The GRI Sector Standards, which are applicable to specific sectors, and;

- The GRI Topic Standards, which are each dedicated to a particular topic and listing disclosures for that topic.

Altogether, the combination of these three standards ensures the versatility of the GRI Standards and provides flexibility for differing needs.

The Practical Guide to Sustainability Reporting Using GRI and SASB Standards notes that the GRI supports broad and comprehensive disclosures on organizational impacts, in contrast with the SASB’s focus on a subset of financially material issues.

Requirements

There are nine requirements for reporting in accordance with the GRI Standards.

If all requirements are not met fully, the organization issuing the sustainability information cannot claim that the information is in accordance with the GRI Standards.

Instead, they may indicate that the reported information was prepared with reference to the GRI Standards.

The GRI Universal Standards GRI 1 also provides guidance for the required procedures for ‘Reporting with reference to the GRI Standards.’

- Apply the reporting principles

- Report the disclosures in GRI General Disclosures 2021

- Determine material topics (Note that the GRI Standards adopts a double materiality approach—standards and frameworks sometimes differ in their definition of materiality)

- Report the disclosures in GRI 3: Material Topics 2021

- Report disclosures from the GRI Topic Standards for each material topic

- Provide reasons for omission for disclosures and requirements that the organization cannot comply with

- Publish a GRI content index

- Provide a statement of use

- Notify GRI

Key concepts and principles

The four key concepts for the GRI Standards are listed in the GRI 1: Foundation 2021 document:

- impact

- material topics

- due diligence

- stakeholders

The GRI Standards also identifies eight reporting principles that are essential for high-quality sustainability reporting. These principles, listed below, guide the quality and presentation of the reported information. Specific guidance on application of said principles is included in the GRI 1, as well as some suggested best practices for reporting.

- Accuracy

- Balance

- Clarity

- Comparability

- Completeness

- Sustainability context

- Timeliness

- Verifiability

Alignment with other frameworks and requirements

The GRI Standards are aligned with intergovernmental instruments, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the ILO conventions, and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

Thus, organizations can use the GRI Standards as a blueprint for applying the aforementioned instruments, as well as for reporting out on progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). GRI developed guidance SDG integration after the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Moreover, the GRI Standards are compatible with standards, frameworks, and initiatives issued by other organizations.

This page links the 2016 version of the Universal Standards (not yet updated for the revised Universal Standards) with related sustainability initiatives such as the SDGs, the SASB Standards, BLab Impact Assessment, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), and more.

Tools and resources

The GRI Standards offers a number of tools to support companies doing sustainability reporting.

Their website includes an FAQ for general questions, a GRI content index template, and an inventory of certified software partners by country, among other resources.

Moreover, as the GRI Standards are marketed as a free public good, the tools mentioned here are available on the GRI website at no cost (at this time, resources are mainly available in English).

GRI certification processes are also available to third party software or tool providers who want to be GRI-approved, along with a document on GRI’s pricing policy for certification.

Recognition

The GRI Standards are widely recognized in the sustainability field, as well as specifically incorporated into other third-party sustainability assessments, such as Ecovadis.

Thus, information that is gathered and presented in accordance with the GRI Standards will likely garner high sustainability ratings.

Who uses the GRI Standards, and why?

All organizations are eligible to use the GRI Standards. Due to the modular nature of the Standards, organizations of any size, sector, and public/private orientation can find relevant guidance and tailor it to their needs.

Individuals such as reporters, stakeholders, and other interested parties may also draw on the Standards for reference.

Benefits of using the Standards for for-profit companies

Potential benefits of using the GRI Standards are positive company reputation and increased stakeholder satisfaction.

For instance, a 2017 joint study by the Government & Accountability Institute and Baruch College/CUNY found that out of 572 total companies, the 481 companies that utilized the GRI Standards scored higher on information quality and degree of verification of ESG disclosure than the 91 counterparts who did not use the Standards.

Applying the GRI Standards to sustainability reporting also helps companies gain a deeper understanding of their material issues, as the Standards provide a blueprint for high-quality data collection and thorough reporting.

This understanding will aid companies in other endeavors, such as risk assessment and future projections.

Moreover, as ESG reporting becomes more commonplace in the private sector, many stakeholders (such as consumers, investors, and employees) are coming to expect some sort of formal sustainability reporting process as a matter of due diligence.

The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance reports that over 96% of 2021 Sustainability Reports included a letter from the CEO, signaling to stakeholders that ESG is a priority for senior leadership.

76% of 2021 Sustainability Reports were accompanied by a press release publicizing the data, and a majority of companies also included a materiality matrix in their reports to provide stakeholders with more detailed insight into the company’s sustainability strategy.

Given that the GRI Standards was the first globally accepted sustainability standard, it is a reliable starting point especially for companies that are looking to get started with sustainability reporting.

How to apply the GRI Standards

Process overview

The GRI reporting process is fairly open-ended in that GRI provides guidance and hard requirements via its Standards documents, but otherwise lets individual organizations determine the details of the process according to their needs.

The graphic is from the GRI Standards introduction document, and lays out the typical steps for reporting under the GRI Standards.

The GRI does not require an audit phase, and there is no set timeline for the assessment. The GSSB does set out a new work program (involving projects to review existing Standards and develop new ones) every three years to keep the GRI Standards up to date.

Thus, it is recommended that companies using the GRI Standards review and publish their data at least every few years—mostly in sustainability reports (whether associated with the GRI Standards or otherwise) are published annually, in any case. Reports must contain a GRI content index.

The content index makes reported information traceable and increases the report’s credibility and transparency.

GRI recommends that organizations report in accordance with the Standards, meaning that the organization reports on all its material topics and related impacts and how it manages these topics.

However, if this is not feasible, the organization can choose which content of the GRI Standards to apply and report with reference.

What changed in the 2021 revised Universal Standards?

The Universal Standards were revised following recommendations from the GRI Technical Committee on Human Rights Disclosure (a stakeholder group for labor-related disclosures).

The revisions were developed according to a set of mandatory requirements for standard development, and were overseen by the GSSB Due Process Oversight Committee and approved in July 2021.

The changes will officially come into effect on January 1, 2023, although GRI encourages earlier adoption when possible.

The main goals of the revision were to:

- incorporate mandatory human rights-related disclosures for all reporting organizations;

- integrate due diligence reporting;

- clarify GRI Standards key concepts, reporting principles and disclosures, ensuring that they align with recent developments in responsible business conduct;

- drive consistent application;

- encourage more relevant and comprehensive reporting;

- and improve the overall usability of the GRI Standards.

Ultimately, the revision led to several key changes, namely:

- setting expectations for responsible business conduct in intergovernmental instruments;

- consolidation of reporting approaches (there is now only one way to report in accordance with the GRI Standards, where previously GRI offered ‘Core’ and ‘Comprehensive’ options);

- key concepts for the foundation of sustainability reporting;

- a revised process for determining material issues;

- revisions to reporting principles, disclosures, as well as updates to structure/language of the Universal Standards, the GRI Standards system, and the addition of templates.

Options for facilitation and aid from third-parties

With apiday, it’s easier than ever to align your reporting with any ESG framework! Including GRI standards.

Our AI driven technology gathers all your sustainability data in one place and automates the reporting process: on the apiday platform, you’ll find a list of documents to share. Upload as many as you can find, and we’ll pre-fill your sustainability report wherever possible and provide you with a correspondence table.

While our experts provide you along the way with tailored ESG consulting support!

Save yourself time and hassle, give us a call and let apiday do the rest!

Impact - What is Impact

Definition

The most widely used definition of impact is the one from the Impact Management Project, which is the same as that of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

It is defined as positive and negative, primary and secondary long-term effects produced by an intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended.

The Global Reporting Initiative defines ‘impact’ as the extent to which an organization affects the economy, society and/or the environment. This can indicate its contribution (positive or negative) to sustainable development.

The term ‘impact’ can refer to any of the following: positive, negative, actual, potential, direct, indirect, short-term or long-term impacts.

Various international organizations define impact in their own ways.

To learn more about Impact...

CSRD - What is CSRD

Definition

On April 21st, 2021, the European Commission issued a draft Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) proposal, which amends the current Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD).

It enables investors, customers, legislators, and other stakeholders to assess the non-financial performance of major organisations.

As a result, it aims at pushing these enterprises to adopt more responsible business practices.

Timeline

While the Directive has been subjected to several delays and modifications, and further clarification is required for its future dates, the following are the major milestones, including gradual implementation over several years, for CSRD:

- April 21st, 2021 – Proposal of the CSRD by the European Commission

- April 2022 - The EFRAG issued its first set of EU sustainability reporting standards (ESRS) open for public consultation until August 2022

- By October 2022 - The EFRAG will release the final set of ESRS

- From January 1st, 2024 - Entry into force of the new CSRD reporting requirements for companies already subject to a non-financial reporting obligation under the NFRD (large listed companies with over 500 employees)

- From January 1, 2025 - Reporting requirements for all large companies meeting 2 of the following 3 criteria: 250 employees, €40 million in revenues, or €20 million in balance sheet

- From January 1, 2026 - Reporting requirements for listed SMEs (10 to 250 employees), with the possibility of deferring their reporting obligation for 3 years with a lighter standard.

- From January 1, 2028 - Reporting requirements for European subsidiaries of non-European parent companies with a turnover of more than €150m in Europe.

CSRD Today

While most actors supported the CSRD proposal, some expressed their concerns around the potential for exacerbating the scope and time mismatch between some reporting requirements that financial institutions may be expected to comply with and the reporting obligations placed on the SME borrowers and investee enterprises of financial institutions.

Moving forward, sustainability should be a top priority for major corporations’ boards of directors. The challenge ahead of businesses in fulfilling this commitment should not be underestimated and requires prompt and cautious attention.

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive: All you need to know

The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive is a European Union law that will have a huge impact on how organisations report their environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance.

The CSRD was introduced on January 1, 2020, and will affect organisations that have a listing on a regulated market in the European Union or that reach certain thresholds (number of employees, turnover, balance sheet).

The new directive will require organisations to publish more information about their environmental impact, social and economic performance, as well as governance practices.

The reports must also include information about the risks and opportunities associated with these areas.

In this article we explain what the directive is, who it affects and the steps you can take to prepare for its enforcement.

Background

In order to achieve the EU’s goal of becoming net-zero by 2050, the European Commission recognizes that private capital must be directed toward green, sustainable projects.

To accomplish this, the Commission believes that investors must have direct exposure to complete and coherent information on their potential investees, including information on environmental practices, social responsibility and governance mechanisms.

The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) represents one key legislation piece that will facilitate the transition towards a more sustainable society, aiming to fill in the gaps in sustainability reporting.

It completes two other regulations which go in the same direction: the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the EU Taxonomy.

Overall, the CSRD will supersede and complement the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). Directive 2014/95/EU Directive 2014/95/EU, which is referred to as the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), sets forth the regulations on disclosure of non-financial and diversity data by certain major firms.

NFRD came into force in all EU member states in 2018. All 27 nations had subsequently adopted the Directive into national legislation, and it is now up to corporations to comply.

It compels some major corporations to provide a non-financial statement as part of their yearly public reporting responsibilities.

With the NFRD, the European Union aimed to accomplish two major goals: make non-financial information about a company’s value creation as well as its risks available to stakeholders and investors, and effort to improve to assume accountability for social and environmental concerns.

From NFRD to CSRD

The Non-Financial Reporting Directive’s reporting requirements set critical criteria for some major corporations to report on their sustainability performance on an annual basis.

It established a double materiality viewpoint,’ which requires businesses to report on the effect of sustainability challenges on their operations as well as their own impact on people and the environment.

Nonetheless, abundant evidence was shared that the data provided by businesses is insufficient. Investors and other stakeholders often believe that reports exclude critical information.

Comparing reported data from one organisation to another may be difficult, and users of the data are sometimes uncertain about its reliability. Quality issues in sustainability reporting have a cascading impact.

As a result, investors lack a comprehensive perspective of the sustainability risks exposed to businesses.

Investors are becoming more interested in the social and environmental effect of businesses.

They need this knowledge in part to comply with the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation’s own disclosure obligations.

More broadly, investors must understand the sustainability effect of the firms in which they participate if the market for green investments is to be viable.

Without such information, funding for ecologically beneficial initiatives cannot be directed.

Finally, deficiencies in reporting quality create an accountability chasm.

Companies that provide high-quality and dependable public reporting will contribute to the development of a more effective disclosure ecosystem.

CSRD precisely aims to dramatically broaden the scope of the NFRD while also increasing the transparency of business progress in terms of long-term sustainability and environmental protection.

The full requirements of the reporting duties under the CSRD will be specified in the new sustainability reporting standards that are currently being finalised under the supervision of the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), which is a private organisation founded in 2001 at the European Commission’s request to serve the public interest.

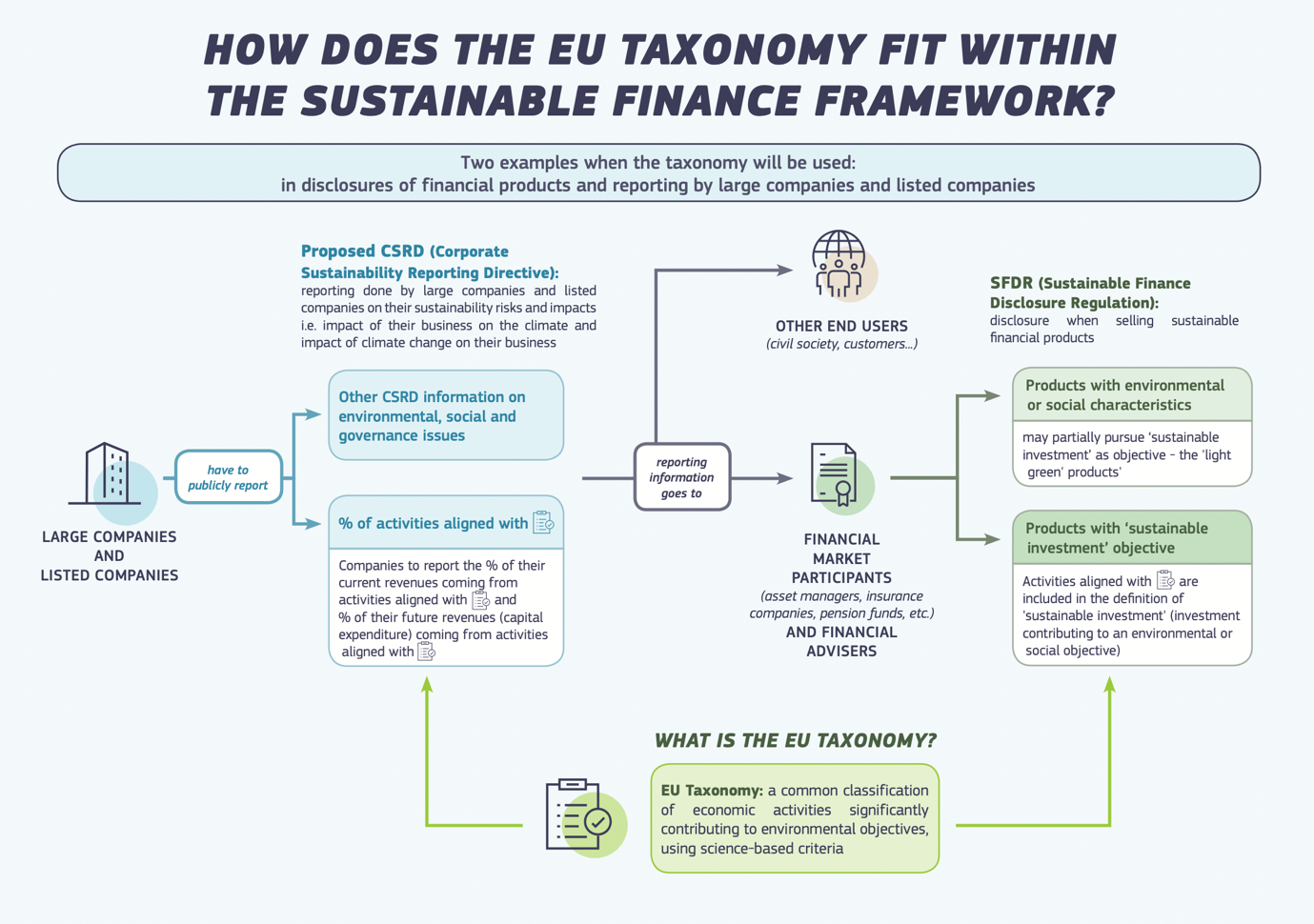

CSRD, SFDR and the EU Taxonomy

The CSRD may be seen as one of three EU rules governing sustainability reporting, alongside SFDR and the EU Taxonomy. The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) came into force in March 2021.

By standardising sustainability disclosures, the SFDR aims to assist institutional investors and clients in understanding, comparing, and monitoring the sustainability features of investment funds.

The EU Taxonomy Regulation was published in the European Union’s Official Journal on 22 June 2020 and adopted on 12 July 2020.

It lays the groundwork for the EU Taxonomy by outlining four broad criteria that an economic activity must fulfil in order to be considered environmentally sustainable.

Whereas the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) is intended to steer investments into sustainable economic activity, the EU Taxonomy determines which economic activities are really “sustainable”.

Article 8 of the Taxonomy Regulation compels enterprises covered by the current Non-Financial Reporting Directive – as well as any new companies covered by the CSRD – to report on the sustainability of their operations. Companies will be required to submit these metrics in addition to other sustainability data required by the CSRD.

Hence, these three regulations are inextricably linked: corporations subject to CSRD are required to make Taxonomy-related disclosures; their reporting is routed via financial market participants, who are subject to SFDR reporting obligations that include Taxonomy-related disclosures as well.

As a result, concerned firms may anticipate increased pressure from investors to publish sufficient sustainability information in accordance with the CSRD and the EU Taxonomy.

Intertwining of the 3 key regulations on non-financial reporting in Europe:

Source: European Commission

Objectives

The CSRD aims to build upon the existing objectives of the NFRD.

The following are the aims of the proposal:

- Requiring that reported information be compatible with EU legislation, including the EU Taxonomy, be comparable, trustworthy, and simple for interested parties to access and utilise using digital technologies.

- Eliminating wasteful expenditures and allowing businesses to fulfill the rising demand for sustainability reporting in a cost-effective way.

CSRD: Scope of Application

The CSRD will broaden the scope of sustainability reporting obligations to include all major businesses that do not meet the NFRD’s existing 500-employee criterion.

All significant firms will be held publicly responsible for their effect on people and the environment as a consequence of this evolution. NFRD applies to “large” public interest entities (“PIEs”).

PIEs are classified as those organisations who have had more than 500 workers in the prior financial year.

The NFRD also absolves subsidiaries from reporting responsibilities if that entity’s parent firm agrees to perform the reporting obligations on behalf of the whole group.

Once operational, the CSRD would expand non-financial reporting obligations to big private corporations as well as those listed on EU regulated markets.

Approximately 12,000 businesses are presently subject to the Non-Financial Reporting Directive.

The European Commission predicts that this figure might climb to around 49,000 under the CSRD, owing to the greater definition of “large undertaking” under the Directive, as opposed to the large PIEs under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive.

Companies who fulfill two of the three requirements outlined below will be required to comply with the CSRD:

- Net turnover of more than €40 million.

- Balance sheet assets greater than €20 million

- More than 250 employees

CSRD has been established to encompass all major and publicly traded corporations operating on EU-regulated marketplaces (except for micro-enterprises).

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) listed on the EU regulated markets have to comply with the CSRD but on an extended schedule.

Additional requirements for CSRD compliance apply to non-EU-based corporations having subsidiaries in the EU and companies that are not formed in the EU but have securities listed on EU-regulated markets.

Practical requirements under CSRD

The following are the most paramount implications brought forward by CSRD:

- broadens the scope to include all major firms and all publicly traded companies on regulated marketplaces (except listed micro-enterprises)

- increases reporting requirements and standardisation of disclosure, including a requirement to report in accordance with mandatory EU sustainability reporting standards that are in the process of being finalised. This will allow comparability of data between disclosing companies

- requires auditing (assurance) of reported information

- requires businesses to digitally 'tag' reported information, making it machine-readable and feeding into the European single access point envisaged in the capital markets union action plan.

Information that should be disclosed by companies

Under CSDR, the Commission currently suggests that obligatory disclosures be included in a company’s management report and address three reporting areas:

1. Strategy

- Business model and strategy

- Primary risks regarding sustainability issues and dependencies

- Management and supervisory bodies' roles in relation to sustainability

2. Implementation

- Due diligence procedures for operations and the supply chain

- Policies addressing sustainability factors

- Sustainability targets

3. Performance

- Indicators pertinent to measuring all of the above

- Progress toward meeting targets

The CSRD covers all ESG criteria: environmental, social and governance issues.

In particular, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) issued in last April address the following 13 ESG topics:

Environment

- Climate change

- Pollution

- Water and marine resources

- Biodiversity and ecosystems

- Circular economy and resource use

Social

- Own workforce

- Workers in the value chain

- Affected communities

- Consumers and end-users

Governance

- Governance, risk management and internal control

- Business conduct

Lastly, three levels of information are expected:

- Mandatory industry-agnostic disclosures, which have been specified by EFRAG in the cross-cutting ESRS mentioned above.

- Mandatory industry-specific disclosures. Companies will have to report on a series of mandatory standards according to their sector of activity. These are currently being defined and will be published in the form of a Delegated Act in June 2024.

- Company-specific information on issues that the company considers important and that have not been covered in the rest of the sustainability report.

Conceptual guidelines CSRD

CSRD provides guidelines on how to take into account certain key concepts:

- Information quality: requirements on how to ensure quality of sustainability data (e.g truthful representation, comparability, verifiability, etc.).

- Double Materiality: determining both the importance of sustainability issues on the company’s performance (i.e. financial materiality) and the external impacts of the company’s activities on the economy, the environment and people (i.e. impact materiality).

- Time horizon: the reporting period for sustainability information should be consistent with the one retained for financial statements, with additional retrospective and forward-looking information.

- Boundaries and value chain: sustainability data should cover direct and indirect business relationships in the upstream and/or downstream value chain

Reporting under CSRD

As part of the CSRD, financial and sustainability information will be released simultaneously within the management report.

A third-party assurance on the reported information will become necessary.

Moreover, companies will have to digitise and identify their sustainability information to make it accessible via the EU’s forthcoming European Single Access Point (ESAP) database.

Important data will need to be “tagged” or given a “digital label” in order for algorithms to read it more quickly and for stakeholders to exploit and evaluate it.

How to prepare for CSRD

Given the breadth and reach of this law, most companies are likely to be seriously affected. Nonetheless, it is important to mention that for companies under NFRD there is no major change yet, until the regulator will release the final EFRAG Standards in late 2022.

For companies newly under CSRD’s scope, there are several steps to take to facilitate this transition. Businesses will want to get acquainted with the proposal itself and the actual implications of its needs for their firm.

The board of directors should ensure that the management team adequately prepares the firm for the new directive’s implementation, commencing immediately with planning.

While the board of directors will oversee the company’s preparations on a broad scale, the audit committee will play a critical role.

It should supervise the establishment of any new measurement and reporting procedures and the efficacy of the systems and controls in place to assist in guaranteeing the robustness of the information provided.

Since the sustainability reporting requirements are still being developed, businesses will need to begin preparations without knowing detailed requirements.

As a result, businesses should stay informed of any EFRAG findings, interpretations, and communications that provide early insight into how the standards will likely appear.

What is certain right now is that companies need to work on their ESG risks / double materiality analysis and then identify existing policies and KPIs covering those risks, and if none, close the gaps by formalising new ones.

Penalties for non-compliance with CSRD

Each Member State will define penalties for infringements to the CSRD.

The EU Commission has specified that sanctions must be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive” in its draft proposal.

This is generally consistent with the present NFRD. However, the CSRD goes further, requiring member states to implement the following (administrative) measures as well:

- a public declaration describing the infraction and identifying the guilty person/entity;

- a cease-and-desist order against the accountable person/entity;

- an administrative pecuniary penalties against the responsible person/entity.

Audit Requirements

The CSRD proposal establishes a common EU-wide audit (assurance) requirement for submitted sustainability data, assisting in ensuring that provided data is accurate and credible.

While the European Commission’s purpose is to achieve a comparable degree of certainty for financial and sustainability reporting, it has allowed for a gradual approach.

Initially, auditors should give an opinion predicated on a “limited assurance” involvement with the sustainability reporting’s compliance with the CSRD’s criteria, including relevant reporting standards.

It is envisaged that the “limited” guarantee will be changed to a “reasonable assurance” at a later date, after the publication of the sustainability criteria and a review by the European Commission within three years of the CSRD taking effect.

Costs of CSRD

Although the EU plan seeks to “lower the superfluous expenses of sustainability reporting for enterprises,” it is projected that preparers would spend considerable one-time fees as well as recurrent yearly costs in order to comply with the regulation.

The suggestion emphasises that corporations are already facing an increasing financial burden as a result of stakeholders demand for sustainability information.

As a consequence, depending on their size, businesses might realise significant savings by implementing the standards, since the standards eliminate the need for further information requests.

Next steps

- October 2022 - The final set of ESRS will be published by the EFRAG.

- January 2024 - Companies subject to the NFRD's non-financial reporting obligation (large listed companies with more than 500 employees) will be required to disclose accordingly to the new CSRD reporting requirements.

- January 2025 - All companies meeting two of the following three criteria will be subject to reporting requirements: 250 employees, €40 million in revenues, or €20 million in balance sheet.

- January 2026 - Listed small and medium-sized enterprises (10-250 employees) may be able to defer their reporting obligation for up to three years with a lighter standard.

- January 2028 - European subsidiaries of non-European companies with a turnover of more than €150 million in Europe will have to comply with new reporting requirements.

In conclusion…

As regulations become more stringent and the business world becomes more socially and environmentally aware, ESG practices will be mandated.

If your company must comply with the CSRD, you should begin immediately. The deadline is coming up fast, and the fines for noncompliance can be steep.

But it can be a time-consuming and complex process.. And that’s where we come in to help!

Apiday provides a platform that simplifies the data collection process of sustainability metrics and unlocks seamless collaboration.

So you can focus on what matters the most: driving change in your company rather than fetching and crunching data!

Get started and book a call with our ESG experts!

Sustainability - What is Sustainability

Definition

On a purely grammatical level, the word sustainability comes from the root of the word “to sustain” and refers to the ability of something to endure over time, to continue a course without termination.

The concept of sustainability is inevitably linked to time.

From that same etymology also comes the word sustainable which means “able to continue at the same level for a period of time”.

“Same level” highlights a very important notion: the quantity of natural resources and the state of natural ecosystems must not just be protected for today’s human needs and aspirations.

They must be sufficient to guarantee, for future generations, the same prosperous development and the same opportunities as they are today.

Related to the environment and for business and policy use, the term sustainability applies to “using methods that do not harm the environment so that natural resources are still available in the future.”

Sustainability can eventually be defined as “the process of living within the limits of available physical, natural and social resources in ways that allow the living systems in which humans are embedded to thrive in perpetuity.”

History

Sustainability is linked to the stream of thoughts that challenges society’s economic growth.

The Club of Rome, founded in April 1968 by Aurelio Peccei, an Italian industrialist, and Alexander King, a Scottish scientist, is a think tank composed of scientists, economists, businessmen, international high civil servants, heads of state, and former heads of state from all five continents.

It published in 1972 its first report The Limit to Growth, known also under the name of The Meadow report, because of its main authors, ecologists Donella Meadows and Dennis Meadows.

The report concludes that, without substantial changes in resource consumption, “the most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.”

The authors make several proposals:

- On the demographic level, measures such as the limitation of two children per couple

- On the economic level, taxes on industry, to stop its growth and redirect the resources thus levied towards agriculture, services and above all the fight against pollution

For this economy without growth to be accepted, the authors propose to distribute the wealth to guarantee the satisfaction of the main human needs.

The 1973 oil crisis increased public concern about sustainability issues. The report went on to sell 30 million copies in more than 30 languages, making it the best-selling environmental book in history.

Then, in 1983, the United Nations created the World Commission on Environment and Development to study the connection between ecological health, economic development, and social equity. The commission was run by the former Norwegian prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland.

After four years of work, in 1987, the “Brundtland Commission” released its final report, Our Common Future, introducing the concept of sustainable development as “an economic development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” and describing how it could be achieved.

It consolidates decades of work on sustainable development.

Following this path, in 1992, the Rio Earth Summit rallied the world to take action and adopt Agenda 21, a comprehensive plan of actions to be taken globally, nationally, and locally by organizations in every environmental area impacted by humans.

The number 21 represented the goal of attaining long-term progress in the twenty-first century.

The United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) was created in December 1992 to ensure effective follow-up, monitoring, and reporting on the implementation of the Agenda 21’s agreements at the local, national, regional, and international levels.

8 years later, with Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) adopted in 2000 by all 191 United Nations member states and at least 22 international organizations, social justice meets public health & environmentalism.

Finally, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development succeeded the MDGs in September 2015.

Those 17 goals reinforce the universal project and call to action to end poverty in all forms, to protect the planet, and to achieve worldwide peace and prosperity for people, now and into the future.

Sustainability comes from this concept of “sustainable development”.

Sustainability defines a long-term goal: working toward a more sustainable world, while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve this goal.

-

- Cambridge dictionary

- University of Alberta

Discover the latest Sustainability Recent Developments to improve your companies

Sustainability is a concept that evolves due to pressing sustainability challenges, worldwide issues, and its own concept limits. New concepts have emerged to think further and respond better to all the world’s current challenges.

Below are the recent developments and new concept arising from sustainability:

Regeneration

Sustainability is key in the fight against environmental issues, but the planet needs humanity to go one step further: striving not only to prevent harm but to redress that imbalance and regenerate what has been lost.

Sustainable regeneration must replenish and restore its resources, it must “heal” environmental, economic and social wounds. It is not just about limiting negative impact, it’s about having a positive impact.

To achieve this, companies must take regenerative actions.

It can be not just taking zero deforestation commitment, but also working to reforest and regenerate ecosystems, or not just paying properly workers and farmers, but also allowing them to develop their business and have a positive long-term impact benefiting a larger community.

Planetary boundaries

In 2009, Johan Rockström, a Swedish internationally recognized scientist for his work on global sustainability, led a group of 28 internationally renowned scientists to identify the processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system.

The scientists proposed a set of 9 quantitative planetary boundaries within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come.

Crossing these boundaries increases the risk of generating large-scale abrupt or irreversible environmental changes.

The 9 planetary boundaries are:

1. Stratospheric ozone depletion

The decrease of the stratospheric ozone layer in the atmosphere filter out ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. This can cause a higher incidence of skin cancer in humans as well as damage to terrestrial and marine biological systems.

2. Loss of Biosphere Integrity (Biodiversity loss and extinctions)

The human demand for food, water, and natural resources causes severe biodiversity loss and leads to changes in ecosystem services.

3. Chemical pollution and the release of novel entities

Emissions of toxic and long-lived substances such as synthetic organic pollutants, heavy metal compounds, and radioactive materials in the environment.

4. Climate change

Greenhouse gas emissions and concentration in the atmosphere rise to a point where it disrupts the climate-carbon cycle. Earth system thresholds are exceeded to tipping-point where climate-carbon cycle feedbacks accelerate Earth’s warming and intensify the climate impacts.

5. Ocean acidification

CO2 dissolved in the oceans forms carbonic acid, altering ocean chemistry and decreasing the pH of the surface water. This increased acidity reduces the number of available carbonate ions, an essential ‘building block’ used by many marine species for shell and skeleton formation.

6. Freshwater consumption and the global hydrological cycle

Human modification of water bodies includes both global-scale river flow changes and shifts in vapor flows arising from land-use change. Human pressure is now the dominant driving force determining the functioning and distribution of global freshwater systems.

7. Land system change

Land (forests, grasslands, wetlands, and other vegetation types) is converted to human use all over the planet, having serious impacts on biodiversity reduction, water flows, and the biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other important elements.

8. Nitrogen and phosphorus flows to the biosphere and oceans

Nitrogen and phosphorus are both essential elements for plant growth. Their biogeochemical cycles have been radically changed by humans as a result of many industrial and agricultural processes.

9. Atmospheric aerosol loading

Aerosols play a critically important role in the hydrological cycle affecting cloud formation and global-scale and regional patterns of atmospheric circulation, such as the monsoon systems in tropical regions.

Today, humanity has already crossed 5 planetary boundaries:

- Climate change

- Land system change

- Loss of Biosphere Integrity (Biodiversity loss and extinctions)

- Nitrogen and phosphorus flows to the biosphere and oceans (biogeochemical flows)

- Chemical pollution and the release of novel entities

Source: Stockholm Resilience Centre

Doughnut model or Doughnut Economics

Doughnut Economics is a visual framework for sustainable development, shaped like a doughnut, combining the concept of planetary boundaries detailed above with the complementary concept of social boundaries.

It acts as a compass for humanity’s 21st-century challenge: meet the needs of all within the means of the planet.

It was developed by the economist Kate Raworth in her 2012 paper A Safe and Just Space for Humanity and elaborated upon in her 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.

The diagram consists of two concentric rings. A social foundation — to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials, and an ecological ceiling — to ensure that humanity does not collectively overshoot planetary boundaries.

Between these two boundaries lies a doughnut-shaped space that is both ecologically safe and socially just — a space in which humanity can thrive.

The twelve dimensions of the social foundation are derived from internationally agreed minimum social standards, as identified by the world’s governments in the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015.

Source: Kate Raworth

As a systemic model, the doughnut is used and implemented by different actors in society, to adopt new business models.

Sustainability pitfalls

Confusion between “green” and “sustainability”

Over the past years, sustainability has been very often linked to the notion of green growth and “green” arguments and actions, notions that are moreover criticized today because they do not take sufficient account of other critical issues like social responsibility issues or resources availability.

There is a major difference between “Green” which is strictly concerned with environmental health and “Sustainable” which is concerned with environmental health, economic vitality, and social benefits.

This confusion is due to the incorrect use of the terms “green” and “sustainable” synonymously and interchangeably in the public space.

Greenwashing and social-washing

The increasing public consideration for sustainability pushes companies to use the sustainability argument wrongfully and falsely to attract customers and to improve public perception.

Greenwashing uses environmental arguments, while social-washing uses social responsibility arguments.

Washing is used in communication in different ways:

- the use of the argument of sustainable development when the approach initiated by the company is either almost non-existent or very partial, not very solid, not widely deployed among employees

- a message that could mislead the consumer about the real ecological quality of the product or the reality of the sustainability approach.

While greenwashing and more broadly washing are not new, it has increased over recent years to meet consumer expectations for companies’ sustainable commitment and then demand environmentally-friendly and socially responsible goods and services.

Companies must address sustainability issues properly by adopting a robust, sincere, and transparent approach.

And this is where we can help!

With the support of our ESG experts, you can benefit from a custom strategy that fits your company’s unique goals and needs.

If you want to succeed in your sustainable journey… Save time and begin the process today with apiday!

We’ll support you through the whole process and help identify where your energy should be dedicated and how, with a step-by-step roadmap.

So, what are you waiting for?

Get your organization started and book a call now!

GRI - What is the Global Reporting Initiative

Definition

The GRI is an international independent standards organization and currently issues one of the most well-known standards for ESG reporting (GRI Standards).

Some other commonly used ESG standards are the ISO 26000, SASB, and CDP.

ESG reporting standards are a specific category of guidance that provides specific, replicable, and detailed information on best practices for disclosing sustainability information.

Standards are key for sustainability reporting because they provide metrics and regularity to the field, thus creating a common blueprint for making frameworks actionable.

Companies will typically announce the standard that they are using for their reports, but there is currently no universal external verification for whether the standard has been applied well.

Note that the GRI does have a Report Registration System, but this system does not check report content; it only scans for the correct claim language and whether the information through the system process is correctly aligned with the registered report.

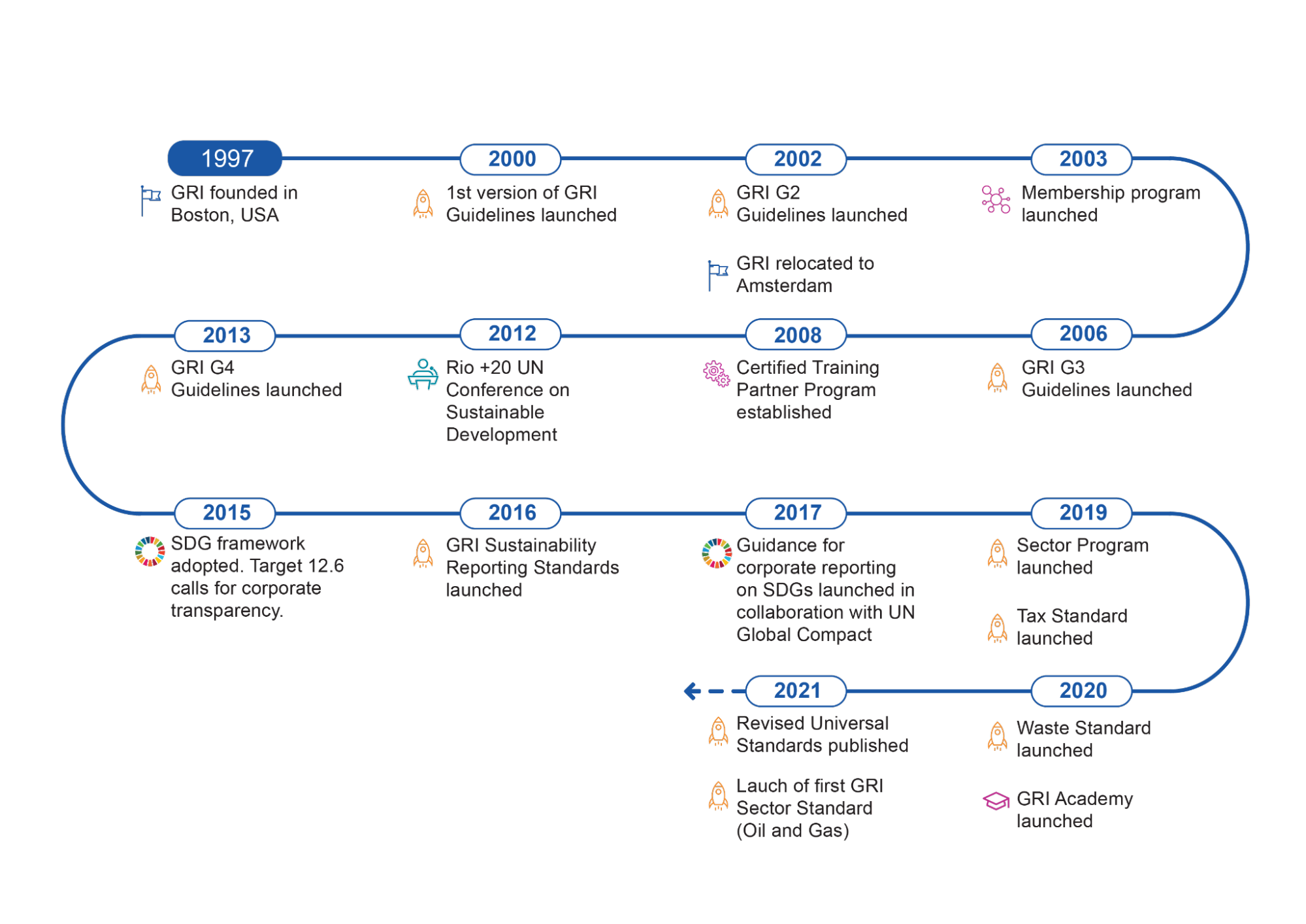

History of the GRI and GRI Standards

The GRI was created in 1997 by two non-profits, Ceres and the Tellus Institute, along with the support of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

The aim of the GRI as a standard setting organization is to enable companies or third parties to assess environmental impact in a cohesive, rigorous way that is widely accepted by others.

The GRI Standards were the first globally accepted standard for sustainability reporting, and are set by the Global Sustainability Standards Board (GSSB), an independent operating entity comprised of 15 members.

Some key dates for the establishment and growth of the GRI Standard include:

- 1997: Founded following the Exxon Valdez oil spill

- 2000: Released first full draft of the Sustainability Reporting Guidelines

- 2008: GRI establishes their Certified Training Partner Program

- 2016: The GRI Standards launched

- 2019-2021: GRI launches the Sector Program, Tax Standard, Waste Standard, GRI Sector Standard, and the Revised Universal Standards

GRI Standards today

Response to demands for clarity in sustainability reporting

In September of 2020, the GRI joined with the SASB, CDP, CDSB, and IIRC to develop a single set of comprehensive and global reporting standards.

The GRI and SASB also started a joint project in the same year, focusing on communication materials to help stakeholders better understand how to use GRI Standards and SASB Standards concurrently.

They have since published A Practical Guide to Sustainability Reporting Using GRI and SASB Standards in April 2021.

GRI Standards growth trends

Overall, the GRI Standards are still the most widely used sustainability reporting standard.

The 2020 KPMG Survey of Sustainability Reporting found that across the world’s largest 250 companies (the G250), the GRI Standards is the only sustainability reporting standard with widespread global adoption.

They also report that as of 2020, 73% of the G250 and 67% of the N100 use the GRI Standards.

However, given the trend towards consolidation and collaboration between the leading sustainability reporting standards, in the future we will most likely see standards being used in synergy, rather than in competition.

Limits and Controversy

Since its introduction, the GRI Standards have been extremely influential.

However, as with all sustainability standards, it faces the challenge of creating a universally applicable Standard while keeping the reporting process straightforward.

Some barriers to the widespread adoption of the GRI Standards, as identified by a researcher from the University of Waterloo, include the general lack of cohesiveness among the different sustainability standards and the necessary interdependence among elements of the GRI Standards (meaning that using the GRI Standards only partially may not be that useful).

The GRI is limited in that it is a topic level reporting framework, meaning that despite the modular nature of the GRI Standards, GRI guidance is still less specific than other reporting frameworks such as the SASB.

The SASB provides instruction on things like disclosure topics and accounting/activity metrics on a granular level, while the GRI has a broader but shallower scope.

Controversy around the GRI mainly centers on whether it accomplishes its goal of providing a single standard for sustainability reporting, and people have different opinions in this regard, with the overwhelming majority supporting it as a respected universal standard.

What is Materiality and Why it matters in business

Materiality is crucial for sustainability reporting because it allows companies to focus on the most important aspects of their sustainability efforts.

A company can choose to report on all aspects of its sustainability program, but this would be extremely time-consuming and would probably not be very useful for investors and other stakeholders who want to know about how a company is handling both its impacts on the environment and society, and how it is impacted by broader ESG issues.

What is Materiality: definition

Materiality refers to identifying the issues that matter most to a company’s business and stakeholders and determining how important they are.

By focusing on material issues, companies can make sure they are reporting on the most important and significant issues so that their reports are useful and informative.

Definitions of materiality vary among ESG frameworks.

Principles and concepts

Objectives behind the concept of impact

At the moment, there are three separate common approaches to materiality:

- financial materiality

- double materiality

- dynamic materiality

Different regions and organizations may favor one approach over the others, although preferences will likely shift and evolve as sustainability reporting advances (see table at the end of this section).

Financial Materiality

- Financial Materiality seeks to identify information that is likely to impact a company’s operating condition and financial performance.

Financial materiality centers investors, and comprises one major perspective on materiality: shareholder-oriented and focused on the external issues that are likely to affect the organization’s financial value.

For instance, a financial materiality approach might consider the issue of corruption material if fines were levied on the company.

The financial materiality approach is common among US and UK regulations and organizations.

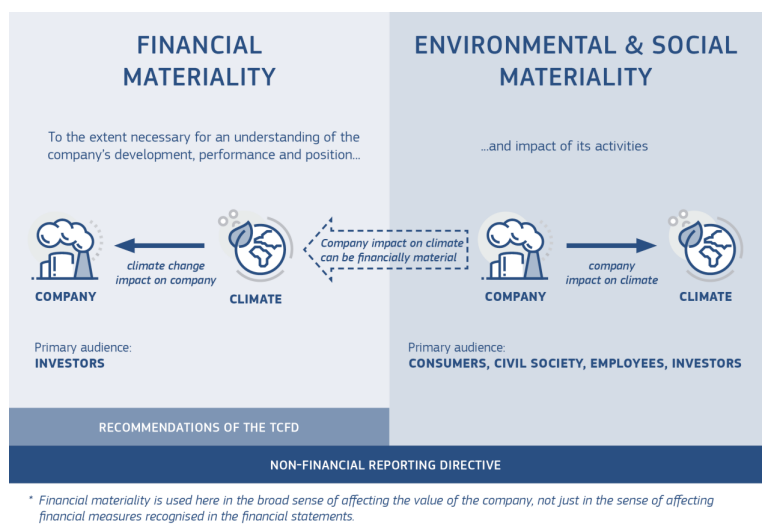

Double Materiality

- Double Materiality is a combination of financial materiality and impact-based materiality.

Impact-based materiality determines materiality by assessing whether a company’s activities might have a significant impact on the economy, environment and people.

For instance, an impact-based materiality approach might consider climate change a material issue for a company that is carbon-intensive, because that company is negatively impacting the environment.

This emphasis on external impacts and a broad set of stakeholders differs from the definition of materiality typically used to guide financial reporting, which is focused on financial impacts of interest to investors.

Given that double materiality incorporates both the financial perspective and the impact-based perspective, the double materiality approach encourages corporations to consider both the impact of a sustainability issue on the company’s value and on stakeholders (economy, environment and people).

The concept of double materiality was first proposed by the European Commission in 2019, and is more commonly adopted in European Union countries.

The Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and the European Financial Reporting Group (EFRAG) both acknowledge double materiality as key sustainability reporting standard-setting.

Source: European Commission, “Guidelines on reporting climate-related information”, 2019.

Dynamic Materiality

- Dynamic Materiality proposes that issues that were not previously considered may become material over time, and that there are certain triggers for this process.

Dynamic materiality is the most recent iteration of materiality, and was first introduced in early 2020 by the World Economic Forum (WEF).

Dynamic materiality takes the perspective that materiality is a process that unfolds over time, rather than a firm designation.

The theory behind dynamic materiality is that businesses in the early stages of growth may negatively impact society because they lack the resources or experience to identify and fully address some issues as material.

However, changing norms such as stakeholder activism, regulations, and/or corporate innovation may eventually motivate the company to adjust their materiality assessment and take action on the issues that they had previously overlooked.

Thus, from the dynamic materiality perspective, materiality evaluations are not static. Rather, materiality assessments present an opportunity for strategic foresight and consideration of external driving forces that may impact the company’s way forward.

Summary table of the positions of renowned ESG frameworks (voluntary or regulatory reporting) on materiality

| Financial Materiality | Double Materiality | Dynamic Materiality |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) | Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) | Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) |

| MSCI Rating System | European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) | Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) |

| International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) | Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Disclosure Recommendations | International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) |

| US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) / Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) | |

| Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) | Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) |

Implications for companies

Materiality assessments are the process by which companies identify and seek to understand the issues that are most important to their practice, given their unique operating concepts.

Materiality analyses are beneficial to corporations in that such analyses can help provide insight into future trends, contribute to the company’s overall risk assessment, and monitor the topics that are important to stakeholders. Materiality assessments also contribute to transparency and accountability in a company’s processes, and therefore, indirectly contributes to stakeholder satisfaction.

Furthermore, not completing a materiality assessment presents financial, reputational, and legal risks. Forgoing a materiality assessment could mean missing key issues, failing to address stakeholders’ concerns, and/or failing to build resilience for future events.

Thus, there is currently a growing demand for materiality analysis, as investors and even governments increasingly see this process as part of a necessary due diligence effort.

A materiality analysis is usually illustrated by a materiality matrix, as shown in the example below.

Source: Unilever

Practical approaches and implementation of materiality assessments

The steps for a materiality assessment may vary depending on the process that the company in question wants to take.

However, the steps below provide an idea of what the process generally looks like.

Identify stakeholders

Gather insights from both:

- Internal stakeholders (eg. Board members, employees, executive leadership, managers, etc).

- External stakeholders (eg. Customers, investors, peer companies, local communities, etc.)

Conduct initial stakeholder outreach

Develop a communication strategy and utilize contextually appropriate outreach channels, either qualitative (interviews with stakeholders) or quantitative (surveys and other hard data collection) – both are necessary to gain a holistic understanding of stakeholder values and expectations.

Design and launch materiality survey

- Identify topics that the company will use to assess/determine priority issues. Material topics are often categorized according to ESG parameters (eg. Environmental, Social, Governance issues), sometimes with the addition of economic indicators.

- Launch and disseminate the survey to relevant audiences

Analyze insights from the survey

Rate the results based upon the predefined scoring methodology. Review both quantitative and qualitative aspects.

The key end result should be a formal matrix graph that plots how each issue ranks in significance relative to stakeholder expectation.

Such graphs, called materiality matrices, are useful in visualizing and mapping out the universe of issues that the company is considering.

Gain necessary approval and support

- Ensure that the materiality analysis results in a clear roadmap (i.e. targets and policies on the most material issues) that is aligned with overall corporate strategy/mission

- Make sure relevant internal and external stakeholders are involved in this roadmap

- Put proper oversight processes into place for accountability purposes

Publicize the results and/or take action

Share the results from the materiality assessment. This is usually done through a formal CSR report, and is later disseminated through channels such as the official company website or other media.

To conclude...

Materiality assessments are crucial to help companies prioritize what needs to be addressed first, so they can focus on the most important aspects of their sustainability efforts, instead of getting distracted.

So, what are you waiting for?

If you want to succeed in your sustainable journey… Save time and begin the process today with apiday!

We’ll support you through your materiality assessment and identify where your energy should be dedicated, with a step-by-step roadmap.

Get your organization started and book a call with our ESG experts!

Materiality - What is Materiality

Definition

Materiality refers to the principle of defining the issues that matter most to a company’s business and stakeholders (ie. the significance of a topic for a company and its stakeholders).

Materiality is key to sustainability reporting because companies have a limited amount of resources and must identify and prioritize the topics that are of greatest importance to their business.

Materiality definitions may vary slightly depending on the organization. The graphic below shows the definitions used by some of the most well-known frameworks in the ESG space.

| Organization | "Materiality" definition |

|---|---|

| Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) | Environmental Information is material if: the environmental impacts or results it describes are, due to their size and nature, expected to have a significant positive or negative impact on the organization’s financial condition and operational results and its ability to execute its strategy: omitting, misstating or obscuring it could reasonably be expected to influence the decisions that users of main-stream reports make on the basis of that mainstream report, which provides information about a specific reporting organization. |

| Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) | An organization is required to identify material topics by considering the two dimensions of the principle: 1) The significance of the organization’s economic, environmental and social impacts - that is, their significance for the economy, environment or society, as per the definition of “impact”- and 2) Their substantive influence on the assessments and decisions of stakeholders. A topic can be material if it ranks highly for only one dimension of the Materiality principle. |

| International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) | In Integrated Reporting, a matter is material if it could substantively affect the organization’s ability to create value in the short, medium and long term. |

| Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) | For the purpose of SASB’s standard-setting process, information is financially material if omitting, misstating, or obscuring it could reasonably be expected to influence investment or lending decisions that users make on the basis of their assessments of short, medium and long-term financial performance and enterprise value. |

Source: the Value Reporting Foundation

History

The concept of materiality in the sustainability field was brought into the mainstream by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 2006.

GRI then published the G3 Guidelines, a cornerstone of the GRI Sustainability Reporting Framework, which identified materiality as one of the four key components for defining sustainability report content.

Materiality has evolved in three clear stages since its introduction.

The first version of materiality emerged from financial environments (ie. the accounting and legal fields) and its purpose was to ensure that shareholders had access to important information about investment risk.

The second evolution of materiality came in concurrence with the newfound interest in CSR and sustainability in the late 20th to early 21st century. This new take on materiality expanded beyond considering the interests of investors—other groups of stakeholders, such as local communities and consumers, were considered as well. However, during the second wave, materiality was still used primarily as a tool for disclosure and transparency.

Most recently, materiality assessments have begun to be used for performance improvement and strategy setting. Stakeholders in search of more detailed information on issues identified as material have set an expectation for thorough materiality analyses in ESG impact assessment.

Recent developments

The definition of materiality (ie. financial, double, or dynamic) is constantly in development, and will likely continue to be debated as organizations seek standardization on sustainability data.

Many boards and frameworks, especially in the EU, have adopted a double materiality perspective, and the idea of dynamic materiality is becoming more widespread as well.

Overall, materiality assessments are becoming more commonplace, with a recent Datamaran study reporting that in 2018, 329 companies with a market capital above $20 billion were doing materiality assessments, compared to only 69 companies in 2011.

One last notable development is the use of automated processing technologies in materiality assessments.

Such technologies enable companies to quickly generate a list of material issues through natural language processing. This advancement, along with the SASB’s sector-specific materiality lists, may also play a role in the development of materiality assessment processes.

EcoVadis - What is EcoVadis rating

Context

Along with the challenge of climate change and the need for companies to drastically reduce their environmental footprint, the question of evaluating the effectiveness of sustainability strategies has become a central concern for business leaders.

As a valuation technique, the international acronym ESG is used by the financial community to designate Environmental, Social and (Corporate) Governance criteria, which generally constitute the pillars of sustainability extra-financial analysis.

Relying on ESG standards and frameworks (GRI, SASB, PRI, etc.), various extra-financial rating agencies have built evaluation grids and metrics along with their own methodology to provide an integrated set of assessment tools to companies.

Based on the information declared by their customers, coupled with other sources such as those of NGOs, trade unions, media, or government entities, these rating agencies can assess the ESG practices of a company regarding the environment and its stakeholders (employees, partners, subcontractors, customers, investors).

Definition

Created in 2007, EcoVadis provides a collaborative web-based rating platform for assessing the sustainability performance of organizations worldwide.

The rating measures an organization’s sustainability management system through 21 criteria focused on four key performance areas:

- Environment (product impact from production processes and product use)

- Labor and human rights (HR management practices, human rights)

- Ethics (corruption, anti-competitive practices)

- Sustainable procurement (supplier environmental and social practices)

EcoVadis today

Each year EcoVadis publishes a “Business Sustainability Risk and Performance Index”, providing comprehensive snapshots of Global Supply Chain ESG performances and evolution.

The 2021 fifth edition was based on data derived from over 72,000 EcoVadis ratings conducted on more than 46,000 companies, covering the period 2016-2020.

Only 7% of rated organizations’ scores are above 64.

Moreover, EcoVadis reveals that “with an overall score of 53.9, companies with multiple EcoVadis assessments outperform the global average of 47.7” meaning that companies that have been assessed by EcoVadis and which regularly use the engagement platform display a steady increase in overall scoring.

Recent developments

In 2020 EcoVadis raised 200 million dollars (180 million euros) from CVC Capital Partners to integrate new technical developments and reinforce its presence in the United States and Asia markets.

In 2021 EcoVadis launched its new “Carbon Action Module” toolbox dedicated to global supply chains.

This module may inform purchasing managers – and more broadly all departments involved in the fight against climate change – about suppliers’ GHG emissions management practices.

Limits of EcoVadis

The EcoVadis score is not a certification but a worldwide trusted notation resulting in a ranking.

The assessment process doesn’t include an audit or an on-site verification, only a desk review of the questionnaire and documentation provided.